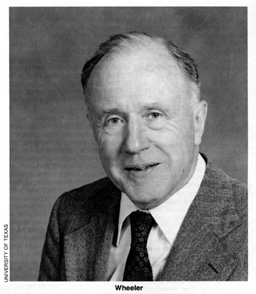

Scientist-philosopher, teacher-cosmologist, father of the Black Hole, Wheeler's thoughts encompass the entire cosmos from the Big Bang to the Big Crunch.

Scientist-philosopher, teacher-cosmologist, father of the Black Hole, Wheeler's thoughts encompass the entire cosmos from the Big Bang to the Big Crunch.

This exclusive interview with John A. Wheeler was made by Mirjana R. Gearhart of COSMIC SEARCH.

COSMIC SEARCH: You have often commented that the greatest discoveries of science are yet to come. What do you have in mind?

Wheeler: To me, the greatest discovery yet to come will be to find how this universe, coming into being from a Big Bang, developed its laws of operation. I call this "Law without Law".* (*Or "Order from Disorder".)

COSMIC SEARCH: Could you explain further?

Wheeler: One of the biggest problems is how to state the problem. It's an old saying that the minute you can state a problem correctly you understand 90 percent of the problem. One of the greatest problems concerns the meaning of measurement or observation. According to quantum theory, measurements can influence what happens. The fact that it is difficult to talk about this problem in an easy way suggests that we have much to learn.

This is a partial response to your question. Putting it another way: How can we possibly imagine the universe with all its regularities and its laws coming into being out of something utterly helter-skelter, higgledy-piggledy and random?

Or, in still another form: If you were the Lord constructing the universe, how would you have gone about it?

COSMIC SEARCH: That certainly is a very deep question.

Wheeler: It's inspiring to read the life of Charles Darwin and think how the division of plant and animal kingdoms, all this myriad of order, came about through the miracles of evolution, natural selection and chance mutation. To me this is a marvelous indication that you can get order by starting with disorder.

COSMIC SEARCH: Do you think there can be any progress on this problem?

Wheeler: One of the conditions, I think, for advance in this field, as in any field, is believing that advance is

possible. What I hope I'm creating is a sense of faith that it can be done. Faith is the number one element. It isn't

something that spreads itself uniformly. Faith is concentrated in a few people at particular times and places. If you can involve young people in an atmosphere of hope and faith, then I think they'll figure out how to get the answer. Faith and hope are absolutely central to everything one does.

You need people who have imagination, daring and the ability to get somewhere. That, to me, is the way research works.

Of course another point to all of this is to keep in touch with key ideas, with what people are doing. Make sure you aren't overlooking something. Here's where it's so important to talk with the young people. Some modest young person comes along with some idea no one else is paying any attention to. His idea may just be the central point.

I'm very fortunate that at Austin, the University of Texas has been willing to finance this kind of work, bringing in two or three people each year for a period of time. So, we'll see what happens.

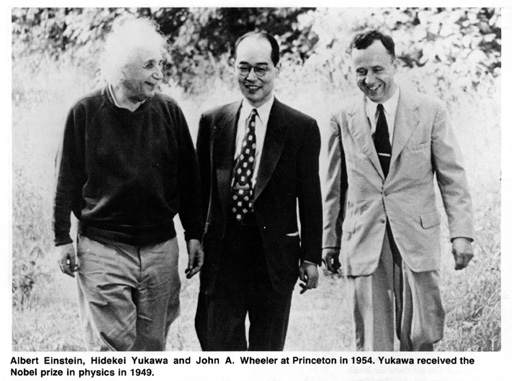

COSMIC SEARCH: You were a colleague of Albert Einstein. We are celebrating the 100th anniversary of his birth this year. When did you first meet him?

Wheeler: October 1933, the month he took up permanent residence in the U.S. was my first meeting with Einstein. Then in 1953, when I first started to teach relativity at Princeton, he was kind enough to invite me to bring my students around to his house for discussions. So, we sat around the dining room table and his secretary, Helen Dukas, and his stepdaughter,

Margot, brought tea and the students asked him questions.

COSMIC SEARCH: Are there some tenets of his that stand out in your mind?

Wheeler: Yes, his work revolved around three rules which apply to all science, our problems, and times:

1. Out of clutter, find simplicity;

2. From discord make harmony; and finally

3. In the middle of difficulty lies opportunity.

COSMIC SEARCH: You began your work in relativity about that time then?

Wheeler: Yes, it was about the period 1952-53-54-55, Einstein's last four years, when I was just getting into relativity. The thing that really got me into it more than anything else was this concern about what happens to a cloud of matter when it collapses. What's the final state?

I had not yet invented the term "black hole". I hadn't yet realized how important it was to attach a name to this concept.

COSMIC SEARCH: How did you come up with the name "black hole"?

Wheeler: It was an act of desperation, to force people to believe in it. It was in 1968, at the time of the discussion of whether pulsars were related to neutron stars or to these completely collapsed objects. I wanted a way of emphasizing that these objects were real. Thus, the name "black hole".

Wheeler: It was an act of desperation, to force people to believe in it. It was in 1968, at the time of the discussion of whether pulsars were related to neutron stars or to these completely collapsed objects. I wanted a way of emphasizing that these objects were real. Thus, the name "black hole".

The Russians used the term frozen star—their point of attention was how it looked from the outside, where the material moves much more slowly until it comes to a horizon.* (*Or critical distance. From inside this distance there is no escape.) But, from the point of view of someone who's on the material itself, falling in, there's nothing special about the horizon. He keeps on going in. There's nothing frozen about what happens to him. So, I felt that that aspect of it needed more emphasis.

COSMIC SEARCH: A few years ago you asked the question: "Are life and mind irrelevant to the structure of the universe, or are they central to it?" Have you found an answer?

Wheeler: No, I'm one of the most baffled men in the world on this subject. There is a line of investigation involving the anthropic (or man-related) principle—the idea that the universe has to be much as it is or life would be impossible. Not only life as we know it, but any life at all would be impossible. On what else can a comprehensible universe be built but the demand for comprehensibility?

My Princeton colleague, Robert Dicke, expressed it this way:

What good is a universe without somebody around to look at it?

That, to be sure, was an old idea, going back not only to the Bishop Berkeley of the time of Newton, but all the way back to Parmenides, the precursor of Socrates and Plato.

But it was new in the form that Dicke put it. He said if you want an observer around, you need life, and if you want life, you need heavy elements. To make heavy elements out of hydrogen, you need thermonuclear combustion. To have thermonuclear combustion, you need a time of cooking in a star of several billion years. In order to stretch out several billion years in its time dimension, the universe, according to general relativity, must be several billion years across in its space dimensions.

So why is the universe as big as it is? Because we're here!

COSMIC SEARCH: A very interesting view.

Wheeler: You could put it another way: You can say there's an efficiency expert who's come to look over the Lord's shoulder. He says,

"Why, Lord, you're wasting a lot of money on this universe. See, you've put one hundred billion (1011) stars in the Milky Way, and you've put one hundred billion (1011 Milky Ways in the universe—that's ten billion trillion (1022) stars—that's a mighty extravagant way to get one planet (the Earth) with life on it so there'll be somebody around to be aware of this universe. Now, Lord, we efficiency people want to cut you down, but we won't cut you down to one star. Instead of 10 billion trillion stars, we'll cut you down to one hundred billion stars—that's enough to make one galaxy. This will be a great economy move."

The only problem is, according to general relativity, when you cut the amount of mass down by a factor of 100 billion, you also cut the size of the universe down by the same amount, just enough universe for one galaxy. You also cut down the time from the Big Bang to the Big Crunch from 100 billion years to just one year which isn't time enough to evolve even one star, let alone evolve life.

Put it another way. There's no obvious extravagance of scale in the construction of the universe. The efficiency expert would have a right to complain if life had been created on several planets, in several parts of the universe, because then he could say that's more than you really need in order for somebody to be around to be aware of the universe. But, if you have life on one planet only (the Earth), then, it's not obvious that you're being extravagant.

The anthropic principle provides a new perspective on the question of life elsewhere in space. It puts in question the common view that the universe is a big machine; that man is unimportant in the scheme of things; that we're an accidental bit of dust

that doesn't have anything to do with it all. From that point of view, it is not very important whether you're going to have life on a billion planets or on just one planet—or no life at all. Life or no life still wouldn't matter in the scheme of the universe.

But, if we adopt this other perspective that Dicke suggests—the anthropic principle—then it's quite a different assessment that we make. Then the universe has to be such as to permit awareness of that universe; otherwise the universe has no meaning.

The anthropic principle looks at this universe, that universe and the other universe and rules out as mere meaningless machines all those in which awareness does not develop somewhere at some time. Stronger than the anthropic principle is what I might call the participatory principle. According to it we could not even imagine a universe that did not somewhere and for some stretch of time contain observers because the very building materials of the universe are these acts of observer-participancy. You wouldn't have the stuff out of which to build the universe otherwise. This participatory principle takes for its foundation the absolutely central point of the quantum:

No elementary phenomenon is a phenomenon until it is an observed (or registered) phenomenon.

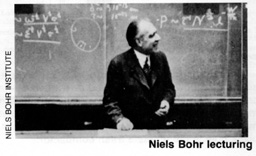

COSMIC SEARCH: You also collaborated with Niels Bohr. Could you tell us about him?

Wheeler: As a student in 1934, I applied for a fellowship to go to Copenhagen to study with Bohr. I remember writing down my reason on the application:

Wheeler: As a student in 1934, I applied for a fellowship to go to Copenhagen to study with Bohr. I remember writing down my reason on the application:

"Bohr sees further ahead in physics than any other man alive".

My fellowship was granted and the next year I went to study with Bohr, the great leader of physics and father-figure of all physicists. There in Copenhagen, Christian Møller, just back from Rome, reported Fermi's results on the capture of slow neutrons. Bohr immediately became terribly concerned, and interrupting Møller, talked and talked while walking back and forth. All the while you could see the liquid drop model of the nucleus taking shape right there before your eyes. For him no physics was of any interest unless it yielded some paradox or some beautiful way of seeing things simply.

My fellowship was granted and the next year I went to study with Bohr, the great leader of physics and father-figure of all physicists. There in Copenhagen, Christian Møller, just back from Rome, reported Fermi's results on the capture of slow neutrons. Bohr immediately became terribly concerned, and interrupting Møller, talked and talked while walking back and forth. All the while you could see the liquid drop model of the nucleus taking shape right there before your eyes. For him no physics was of any interest unless it yielded some paradox or some beautiful way of seeing things simply.

I do not remember anyone at Bohr's institute who ever succeeded in finishing a seminar talk, even though he was the invited speaker. He might be able to speak fifteen minutes, but soon Bohr would take over and would use the whole time discussing the meaning of the speaker's results and what they proved or disproved.

COSMIC SEARCH: You were also involved with Bohr later, weren't you?

Wheeler: Yes, I was down at the pier in New York on January 16, 1939, to meet him, and I had hardly said "Hello" when I learned that just before his ship left Copenhagen, he had been told of the discovery of nuclear fission by Hahn and Strassmann. So we dropped everything else and started to work on fission.

During the war I met Bohr in Washington at the time he was dividing his time between Los Alamos and Washington. He told me confidentially about his discussions with President Roosevelt about the future of nuclear energy. He told me about his efforts to work out some kind of control of nuclear energy after the war.

During the war I met Bohr in Washington at the time he was dividing his time between Los Alamos and Washington. He told me confidentially about his discussions with President Roosevelt about the future of nuclear energy. He told me about his efforts to work out some kind of control of nuclear energy after the war.

Bohr made a great impression on Roosevelt and they had several discussions. The last speech Roosevelt wrote—he died while he was still working on it—had in it some words, quoted by Roosevelt from Thomas Jefferson, about how scientists serve as indispensable means of communication for bringing peace between different countries of the world.

It was enormously impressive to me to see Bohr's courage in facing up to what the great questions were. I can vividly remember him saying to me:

"I must always seem to you like an amateur. But I am always an amateur."

Of course, that is a very modest way of saying that one is a pioneer, an explorer. If you are working on something new, then you are necessarily an amateur.

COSMIC SEARCH: Niels Bohr created one of the world's most influential schools of modern physics in Copenhagen. You, too, have educated many leading physicists, both in nuclear physics and in general relativity, at Princeton. Do you have some

thoughts about educating students?

Wheeler: Shouldn't you rephrase your question? After all, I'm sure that it is really the students who educate me! We all know that the real reason universities have students is to educate the professors. But, in order to be educated by the students, one has to put good questions to them. You try out your questions on the students. If there are questions that the students get interested in, then they start to tell you new things and keep you asking more new questions. Pretty soon you

have learned a great deal.

COSMIC SEARCH: What insights can one gain from the collapse of a star into a black hole as regards the ultimate collapse of the universe?

Wheeler: I would regard the black hole as a here-and-now model for the collapse of the universe. We've come to

recognize that in the typical closed-model universe, a black hole that forms at some point in the history of the universe is not a singularity—a Gate of Time—separate and distinct from the Big Crunch, but is part and parcel of the same thing.

Let me put it this way. If you'll permit, let's imagine ourselves as in an ice cave, and let's think of time as pointing upward from the floor. The floor of ice represents the Big Bang. The roof of ice represents the Big Crunch—and some spikes hanging down, icicles, represent black holes. Think of water gradually filling the cave as it comes up, representing the advance of time. No water, and you're back at the Big Bang; a little water, and you're in the early days of the universe. More water and your time level is where we are now. As the water rises—as time goes on—it engulfs a few of the spikes, the icicles—that's the moment when black holes are formed. Keep the water level going on up and you get to the point where the spikes are completely immersed and the water even reaches to the top of the cave. Then you have arrived at the Big Crunch. From this point of view, you can see that the Big Crunch or final Gate of Time is not distinct in nature from the black hole. They're the same kind of animal. In that sense, learning about a black hole is learning about the final stages of the universe.

Let me put it this way. If you'll permit, let's imagine ourselves as in an ice cave, and let's think of time as pointing upward from the floor. The floor of ice represents the Big Bang. The roof of ice represents the Big Crunch—and some spikes hanging down, icicles, represent black holes. Think of water gradually filling the cave as it comes up, representing the advance of time. No water, and you're back at the Big Bang; a little water, and you're in the early days of the universe. More water and your time level is where we are now. As the water rises—as time goes on—it engulfs a few of the spikes, the icicles—that's the moment when black holes are formed. Keep the water level going on up and you get to the point where the spikes are completely immersed and the water even reaches to the top of the cave. Then you have arrived at the Big Crunch. From this point of view, you can see that the Big Crunch or final Gate of Time is not distinct in nature from the black hole. They're the same kind of animal. In that sense, learning about a black hole is learning about the final stages of the universe.

Although many articles are being written about the outsides of black holes, hardly any deal with the question of what happens inside the black hole, on the way to the Big Crunch. All the indications I can see point to it being the direct opposite of what happens on the outside. The outside settles down to a steady standard condition. If it's perturbed a little bit away

from that ideal state, it once again reverts to the steady condition.

But, on the inside, the condition is the exact opposite, in the sense that if the collapse of matter is not exactly symmetric, then the perturbations from the infalling matter will get worse and worse, and bigger and bigger. There will be so-called "mixmaster" oscillations. Matter—and space geometry as well—will be driven into a gigantic chaos. If, as we believe, the black hole is really part and parcel of the final singularity, then these "mixmaster" oscillations should be a

common property of black holes and the big crunch. We have much to learn from studying this chaos from the theoretical end. That doesn't mean these extreme conditions have no observational consequences; they certainly do.

One might question this point. One might ask, what sense is it to talk about the physics inside a black hole? Who's ever going to fall inside a black hole? But, here we are living inside—if Einstein is correct—a closed universe, and we will eventually head into a Big Crunch ourselves—so the laugh's on us!

COSMIC SEARCH: If that is true—that the last laugh is on us, how does that affect mankind's attitude?

Wheeler: If the universe is only going to last for a finite time, I think it's far too early in the scheme of things to try to draw conclusions about how we should react. We're still so much in the learning phase. We have to keep separate what we're learning from our attitudes.

To me to live a one-life-only in a one-life-only universe provides a poetic parallelism. How precious life is! Every day, every person one meets, every experience—that's all we're going to have. It distresses me that so many people go through life in an alienated spirit, not realizing that this is the only opportunity they have—they'll never have it again.

COSMIC SEARCH: We certainly are at a very important time in mankind's thinking about its place in the universe. Thank you, Professor Wheeler, for sharing with us a glimpse of these great discoveries yet to come.

John Archibald Wheeler has been at the forefront of theoretical physics for nearly five decades. In the 1930's, with

Niels Bohr, he developed the first general theory of nuclear fission. In the 1940's, with a student, Richard Feynman, he discovered a new approach to electrodynamics which has proven to be of great value. In the 1950's he found new solutions to Einstein's gravitational equations of importance in astrophysics. In the 1960s he pioneered studies involving gravitational collapse, neutron stars and Black Holes (a name he invented). More recently Wheeler has proposed and analyzed "delayed

choice" experiments. In them a difference in what one measures on the particle—or photon—now makes an irretrievable difference in what one has the right to say the particle already did in the past. This effect, which makes it impossible to monitor the events of nature with complete detachment, he calls "observer-participancy".

John Archibald Wheeler has been at the forefront of theoretical physics for nearly five decades. In the 1930's, with

Niels Bohr, he developed the first general theory of nuclear fission. In the 1940's, with a student, Richard Feynman, he discovered a new approach to electrodynamics which has proven to be of great value. In the 1950's he found new solutions to Einstein's gravitational equations of importance in astrophysics. In the 1960s he pioneered studies involving gravitational collapse, neutron stars and Black Holes (a name he invented). More recently Wheeler has proposed and analyzed "delayed

choice" experiments. In them a difference in what one measures on the particle—or photon—now makes an irretrievable difference in what one has the right to say the particle already did in the past. This effect, which makes it impossible to monitor the events of nature with complete detachment, he calls "observer-participancy".

Wheeler is a scientist-philosopher whose thoughts encompass the entire cosmos from its smallest microstructure to its astronomical maximum, while spanning its past and future between the two "Gates of Time": the "Big Bang" beginning and the Big Crunch" ending. The Gates of Time is also a term he coined. Wheeler's dynamic career gives special meaning to the statement that scientists are even more interesting than science.

Wheeler is Director of the Center for Theoretical Physics at the University of Texas, Austin. Before going to Austin in 1976, he was the Joseph Henry Professor of Physics at Princeton University, where he had been a faculty member for 38 years.

Born in Florida in 1911, he received his doctorate from Johns Hopkins University in 1933. In 1938 he joined the physics faculty of Princeton University where he served until his move to Austin in 1976. Wheeler is past president of the American Physical Society, recipient of the Albert Einstein Prize of the Strauss Foundation (1965), the Enrico Fermi Award for his work on nuclear fission (presented by President Lyndon Johnson in 1968), the Franklin Medal of the Franklin Institute (1969), and the National Medal of Science (1971), as well as numerous honorary degrees.

He is the author of many scientific articles and author or co-author of six books. His famous, monumental 1280-page text "Gravitation" (1973) was written in collaboration with his former students Kip Thorne and Charles Misner; his most recent, "Frontiers of Time", appeared in 1979.

A man of great modesty, Wheeler radiates a contagious enthusiasm coupled with a charming informality. He has a fondness for paradox as epitomized by: "We will first understand how simple the universe is when we recognize how strange it is".

Wheeler on Science:

- "The greatest discoveries are yet to come."

- "What good is a universe without somebody around to look at it?"

- "There's no obvious extravagance of scale in the construction of the universe."

- "If you're working on something new, then you are necessarily an amateur."

- "So, why is the universe as big as it is? Because we're here!"

- "Learning about a black hole is learning about the final stages of the universe."

- "You have to keep separate what we're learning from our attitudes."

- "We will first understand how simple the universe is when we recognize how strange it is."

- "The real reason universities have students is to educate the professors. "

- "You need people who have the imagination, daring and ability to get somewhere. That is the way research works."

- "No elementary phenomenon is a phenomenon until it is an observed phenomenon."

|

![[NAAPO Logo]](../../Images/NAAPOsm.jpg)

![[NAAPO Logo]](../../Images/NAAPOsm.jpg)