Every morning for millions of years sunrise over the chalk plains of Britain illuminated the same landscape. The light washed over gently rolling hills and scattered banks of trees, igniting the eyes of birds and small mammals whose species had been greeting the sun here for millions of mornings. Yet one morning the sun found a stranger standing on the plain, an animal who soon showed that he was different from the animals around him. While other animals used the sunlight to begin foraging for food to satisfy their hunger, this creature only stood and watched the sun, as if the light itself was food that fed a different kind of need, a hunger not of the stomach but of the mind. When the sun disappeared he watched the moon and the other lights in the sky. He watched in every season, through harvests and plagues, for years and decades, and though individuals might age and close their eyes forever, new generations would always lift their faces to the sky.

Every morning for millions of years sunrise over the chalk plains of Britain illuminated the same landscape. The light washed over gently rolling hills and scattered banks of trees, igniting the eyes of birds and small mammals whose species had been greeting the sun here for millions of mornings. Yet one morning the sun found a stranger standing on the plain, an animal who soon showed that he was different from the animals around him. While other animals used the sunlight to begin foraging for food to satisfy their hunger, this creature only stood and watched the sun, as if the light itself was food that fed a different kind of need, a hunger not of the stomach but of the mind. When the sun disappeared he watched the moon and the other lights in the sky. He watched in every season, through harvests and plagues, for years and decades, and though individuals might age and close their eyes forever, new generations would always lift their faces to the sky.

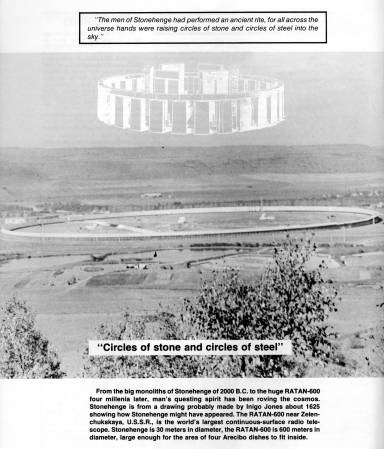

After many generations something strange began happening on the chalk plains. Hundreds of men began bringing massive stones from far away and raising them in a circle. They needed years to break the monoliths out of the earth and drag and heave them inch by inch over miles of hills, but the task could not outlast their determination. With only logs and rope for tools they had to rely on muscles

and sweat to raise the stones, but their aspirations out-

weighed tons of rock.

After many generations something strange began happening on the chalk plains. Hundreds of men began bringing massive stones from far away and raising them in a circle. They needed years to break the monoliths out of the earth and drag and heave them inch by inch over miles of hills, but the task could not outlast their determination. With only logs and rope for tools they had to rely on muscles

and sweat to raise the stones, but their aspirations out-

weighed tons of rock.

Many animals must have noticed the peculiar structure rising nearby, but it could only puzzle them. They might have understood what all this effort was about if the humans had been making a dwelling for themselves, for that was a need shared by every animal, but man was building something that only he could need or understand. Only yesterday on the evolutionary timescale man had been content to roam with his fellow animals in search of food and comfort, but something had happened to him. He had felt something no animal had ever felt, something that made him raise tons of stone into the sky. His organs and muscles and bones had been evolved by millions of animals searching for food and shelter, but now his animal body was serving distinctly human longings.

What set man apart was his discovery of the universe. He had been looking at the earth and the stars for millions of years, but evolution slowly allowed him to see them differently. The familiar terrain where he had always lived began to feel strangely alien. The stars he had noticed without concern came to haunt him with their strangeness. The creature who had been satisfied with food and companionship began to ask what the universe was all about, and he found he could not answer. He looked at the world and saw a bottomless mystery, and his whole life became an enigma.

The void opening in the human mind left man with a loneliness beyond any he had ever known, a cosmic loneliness. There was no one to answer his questions, and perhaps there weren't even any answers. He couldn't ask the animals around him, for where he saw the mystery of the universe, they were busy watching for enemies and sniffing the ground for signs of something to eat. Man was alone with his own thoughts, with questions to answer as well as he could.

Man saw this mystery most awesomely in the sky, and everywhere around Earth human faces turned to follow the lights flying above them. For a long time the sky must have seemed a blur of lights and motion, yet as generation after generation watched, they gradually discerned patterns in the whirling confusion. Though humans might not be able to grasp the meaning of the universe and their lives in it, they could at least begin to unravel the swarm of events around them and know something of how the universe worked. Of first importance was the sun. Though the life of Earth was rooted in the soil, man realized that it flourished or withered depending on the energy raining from the sky. If humans feared that the seasons came and went by whim they must have been greatly reassured to discover that the sun followed a reliable course. Winter would not go on forever: the days would start to lengthen again, and man could know when. He could also know when the smaller lights in the sky would come and go, and even when the moon would pass before the sun and blacken Earth with its shadow. Something profound had happened on Earth: the brains that began as feeble sparks in the primordial seas had come to know of cosmic events before they occurred.

"Though man and creatures elsewhere were born in isolation, all are children of the same universe."

Though knowing their courses, man still didn't know the nature of the lights in the sky. He often conceived of them as powerful personalities responsible for creating and ruling the world. Different groups called these beings by different names, imagined different faces and motivations for them, yet all around the world humans were tracking the same lights and plotting the same paths across the sky.

Humans not only studied the sky, they put a great deal of effort into embodying their discoveries in structures that would be sure to outlast them. Some raised circles of stone whose alignments allowed them to recognize soltices [sic; solstices] or imminent eclipses. Others dug tombs and built temples whose innermost sanctuaries were briefly illuminated on the shortest or longest day of the year. Many raised single archways through which to spot important events, or single stones to mark a steady point from which to watch the sun shift against the features of a mountain range.

Yet stone outlasts civilizations almost as easily as it does individuals. The societies who reflected the sky in mirrors of stone vanished one by one. The Maya suddenly abandoned their great calendars to the jungle. Egyptian culture was strong enough to last thousands of years, but its temples would stand long after the prayers fell silent and the gods were forgotten. Babylon fell into ruin and the tablets containing hundreds ofyears of astronomical patterns were broken and lost. And even when no one was left who knew

how to read it, Stonehenge faithfully carried on the watch of its creators.

Later generations would puzzle over the ruined monoliths of Stonehenge, but if the purpose of the stones was forgotten, the feelings that moved humans to erect them were not.

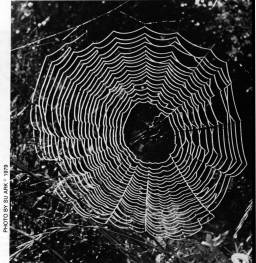

"Sunlight is reflected in the dew of delicate spiderwebs . . .

and in the massive webs of metal hanging in the sky."

(World's largest fully-steerable radio telescope 100 meters in diameter at Bonn, Germany.)

As morning moves across the face of the planet sunlight is reflected in the dew of millions of delicate spiderwebs, and also in hundreds of massive webs of metal hanging in the air, spun not for capturing insects, but a far more intangible kind of nourishment. The webs rise among mountains and beside the sea, from plains and valleys, deserts and tropical islands, amid forests and arctic wilderness, and each points to the sky.

These circles of metal are the work of the same hands that raised Stonehenge, but they are reaching so much farther. Stones could only trace patterns on the surface of the sky, but these webs of woven metal probe the farthest galaxies. The men of Stonehenge were limited by what their own eyes could see, while the people of the radio telescope see the universe through senses humans do not

possess.

Evolution endowed animals with all the senses they needed to live, but man's needs had outgrown anything evolution could imagine or devise. The human body was designed for a habitat of trees and grasslands, but the habitat of the human mind had suddenly grown to include the entire universe. Evolution devised human senses for the life of a primate, yet now man wanted to perceive more than evolution had deemed sufficient. The human brain was no larger than many others on the planet, but the instruments man built to feed the hunger of that brain would dwarf the greatest whales. All around the Earth his great machines absorbed the energies born in the hearts of distant stars, and his mind worked to understand what was happening there.

The universe perceived from the radio telescope is very different from that seen over Stonehenge. The universe had expanded beyond human imagination, and the stars and galaxies had expanded with it. The common swirl of lights around Earth had been dissolved into billions of centers of motion. The universe was filled with bizarre objects pulsing with incredible energies. And instead of watching for gods, man now searched for creatures like himself.

As man's image of the universe changed he realized that he must be only one of many creatures looking out upon the stars. Earth was not the only womb of life in the universe; the same creative forces that gave birth to man were at work in every galaxy. Man now stared into the sky and wondered what strange faces were staring back at him, and what thoughts flickered behind those faces. He could only guess what minds were awakening elsewhere when Earth was still unformed, or what civilizations had arisen among the stars. But now he knew that he was not the first to look into the universe and feel its strangeness. The men who built Stonehenge had unknowingly performed an ancient rite, for all across the universe hands were raising circles of stone and circles of steel into the sky.

"These circles of steel are the work of the same hands that raised Stonehenge but they are reaching so much farther . . . to the farthest galaxies."

Thousands of years of studying the sky have brought man to search for other minds among the stars. The radio telescopes carry on the work of the men who raised stones to mark the sky, but they wait for something the priests of Babylon and Stonehenge could not imagine: not a solstice, but a call from across the light-years, announcing to anyone who might be listening the presence of a mind. Man listens to the heartbeats of the stars, hoping to detect a pulse of consciousness among the roaring energies of the universe.

Though much in man's vision of the universe has changed, one thing has not. Whether humans saw the cosmos from a Stonehenge or a Green Bank, they felt equally amazed to find themselves alive in such a universe. Whether they looked for signs of gods or consciousness, they acted out of the same hunger to know the cosmos in which they had awakened. Man might never be able to understand the mystery of the universe, but he could not rest until he had experienced that mystery as fully as he could.

"Sunlight is reflected in the dew of delicate spiderwebs . . . "

" . . . and in the massive webs of metal hanging in the sky." (World's largest fully-steerable radio telescope 100 meters in diameter

at Bonn, Germany.)

"Man listens for a call from across the light-years, announcing the presence of a mind."

Yet now man might no longer have to face that mystery alone. If no creature of his own planet could share his feelings, there were yet billions of planets scattered among the galaxies. Each was a womb which might conceive a mind sensitive enough to feel the enigma of his own life and the universe that gave him birth. The universe creates these races far apart and leaves them on their own to try to

find one another. When man manages to find creatures like himself somewhere in the enormities of space, his cosmic loneliness will come to an end, for he will join a fellowship of minds who have shared the same experience. Though born in isolation, all are children of the same universe. Though each might be unique, they are joined by the profoundest bond, that of sharing the same enigmatic existence.

Don Lago, 22, resides in Missouri. He has attended college briefly. Beyond that, in his own words, "My occupation is finding out what people who have lived before me have discovered and thought about the world, and occasionally I have an interesting thought of my own. This is a full-time job in itself and doesn't leave much time to waste on such things as making money, which I am doing at a bookstore.

Don Lago, 22, resides in Missouri. He has attended college briefly. Beyond that, in his own words, "My occupation is finding out what people who have lived before me have discovered and thought about the world, and occasionally I have an interesting thought of my own. This is a full-time job in itself and doesn't leave much time to waste on such things as making money, which I am doing at a bookstore.

"I was born on the planet Earth (let's not be provincial), and plan to spend most of my life there. I find it very exciting to be alive when man is first searching for other minds in the universe, and hope to live long enough to learn what they have thought about the cosmos."

![[NAAPO Logo]](../../Images/NAAPOsm.jpg)

![[NAAPO Logo]](../../Images/NAAPOsm.jpg)