Through all of our history we have pondered the stars and mused whether mankind is unique or if, somewhere else out there in the dark of night sky, there are other beings who contemplate and wonder as we do — fellow thinkers in the cosmos. Such beings might view themselves and the universe differently. Somewhere else there might exist exotic biologies, technologies and societies. What a splendid perspective contact with a profoundly different civilization might provide! In a cosmic setting vast and old beyond ordinary human understanding we are a little lonely, and we ponder the ultimate significance, if any, of our tiny but exquisite blue planet, the Earth. The Search for Extra-Terrestrial Intelligence (SETI) is the search for a generally acceptable cosmic context for the human species. In the deepest sense the search for extraterrestrial intelligence is a search for ourselves.

Until recently there could be no such search. No matter how deep the concern or how dedicated the effort, human beings could not scratch the surface of the problem. But in the last few years — in one millionth of the lifetime of our species on this planet — we have achieved an extraordinary technological capability which enables us to seek out unimaginably distant civilizations, even if they are no more advanced than we. That capability is called radio astronomy and involves single radio telescopes, collections

or arrays of radio telescopes, sensitive radio detectors, advanced computers for processing received data, and the imagination and skill of dedicated scientists. Radio astronomy has, in the last decade, opened a new window on the physical universe. It may also, if we are wise enough to make the effort, cast a brilliant light on the biological universe.

Some scientists working on the question of extraterrestrial intelligence, myself among them, have attempted to estimate the number of advanced technical civilizations in the Milky Way galaxy — that is, societies capable of radio astronomy. Such estimates are little better than guesses. They require assigning numerical values to quantities such as the numbers and ages of stars, which we know well; the abundance of planetary systems and the likelihood of the origin of life within them, which we know less well; and the probability of the evolution of intelligent life and the lifetime of technical civilizations, about which we know very little indeed. When we do the arithmetic, the number that my colleagues and I come up with is around a million technical civilizations in our Galaxy alone. That is a breathtakingly large number, and it is exhilarating to imagine the diversity, lifestyles and commerce of those million worlds. But there may be as many as 250 billion stars in the Milky Way Galaxy. Even with a million civilizations, less than one star in 250,000 would have a planet inhabited by an advanced civilization. Since we have little idea which stars are likely candidates, we will have to examine a huge number of them. Thus the quest for extraterrestrial intelligence may require a significant effort.

"A single message from space will show that it is possible to live through technological adolescence."

Despite claims about ancient astronauts and unidentified flying objects, there is no firm evidence of past visitations to the Earth by other civilizations, and so we are restricted to looking for signals from afar. Of the long-distance techniques available to our technology, radio is by far the best. Radio telescopes are relatively inexpensive; radio signals travel at the speed of light, faster than which nothing can travel; and the use of radio for communication is not an anthropocentric activity: radio represents a large

part of the electromagnetic spectrum, and any technical civilization anywhere in the Galaxy will have discovered radio, just as we have. Advanced civilizations might very well use some other means of communication with their peers — "zeta rays," say, which we might not discover for centuries. But if they wish to communicate with less advanced civilizations, there are only a few obvious methods, the chief of which is radio.

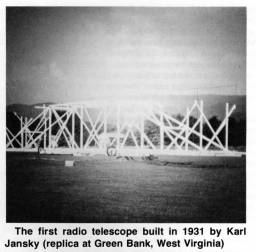

The first serious attempt to listen to possible radio signals from other civilizations was set up at the National Radio Astronomy Observatory in Green Bank, West Virginia, in 1959. This program, organized by Frank Drake who is now at Cornell University, was called Project Ozma [See "A Reminiscence of Project Ozma" by Frank D. Drake, January 1979, COSMIC SEARCH.]; after the princess of L. Frank Baum's Land of Oz, a place exotic, distant and difficult to reach. Drake examined two nearby stars, Epsilon Eridani and Tau Ceti, for a few weeks with negative results. Positive results would have been astonishing, because, as we have seen, even rather optimistic estimates of the number of technical civilizations in the Galaxy imply that several hundred thousand stars must be examined in order to achieve success by random stellar selection.

"It is difficult to think of another enterprise which holds as much promise for the future of humanity."

Since Project Ozma, there have been six or eight other such programs, all at a rather modest level, in the United States, Canada and the Soviet Union. Not one of them has achieved positive results. The total number of individual stars examined to date is fewer than 1,000. We have performed something like one-tenth of one percent of the required effort.

However, there are signs that much more serious efforts may be mounted in the reasonably near future. All the observing programs to date have involved either tiny amounts of time on large radio telescopes or large amounts of time on smaller telescopes. In a major scientific study for the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, directed by Philip Morrison of the Massachusetts Institute of

Technology, the feasibility and desirability of more systematic investigations have been powerfully underscored. The study has four main conclusions:

"(1) It is both timely and feasible to begin a serious search for extraterrestrial intelligence;

"(2) a significant . . . program with substantial potential secondary benefits can be undertaken with only modest resources;

"(3) large systems with great capability can be built as needed; and

"(4) such a search is intrinsically an international endeavor in which the United States can take a lead."

The study carries a reassuring foreword by the Reverend Theodore Hesburgh, President of the University of Notre Dame, that such a search is consistent with religious and spiritual values, and includes the following ringing sentiment:

"The question deserves . . . the serious and prolonged attention of many professionals from a wide range of disciplines — anthropologists, artists, lawyers, politicians, philosophers, theologians — even more than that, the concern of all thoughtful persons, whether specialists or not. We must, all of us, consider the outcome of the search. That search, we believe, is feasible; its outcome is truly important either way. Dare we begin? For us who write here, that question has step-by-step become instead: Dare we delay?"

A wide range of options is identified in the Morrison report, including new (and expensive) giant ground-based and space-borne radio telescopes. But the study also points out that major progress can be made at modest cost by the development of more sensitive radio receivers and of ingenious computerized data-processing systems.

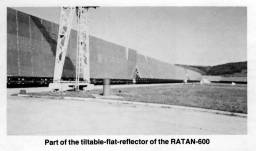

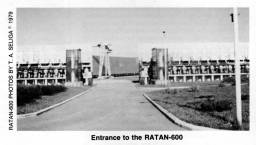

In the Soviet Union there is a state commission devoted to organizing a search for extraterrestrial intelligence, and the large, 600-meter diameter "RATAN-600" radio telescope in the Caucasus, just completed, is to be devoted part-time to this effort. And along with spectacular advances in radio technology, there has been a dramatic increase in the scientific and public respectability of theories

about extraterrestrial life. Indeed, the Viking missions to Mars were, to a significant extent, dedicated to the search for life on another planet.

The large RATAN-600 radio telescope in the Caucasus is to be devoted part-time to SETI.

Of course, not all scientists accept the notion that other advanced civilizations exist. A few who have speculated on this subject lately are asking: if extraterrestrial intelligence is abundant, why have we not already seen its manifestations? Think of the advances by our own technical civilization in the last 10,000 years, and imagine such advances continued over millions or billions of years. If any civilizations are that much more advanced than we, why have they not produced artifacts, devices and even cases of industrial pollution of such magnitude that we would have detected them? Why have these beings not restructured the entire Galaxy for their convenience?

And why has there been no clear evidence of extraterrestrial visits to the Earth? We have already launched slow and modest interstellar spacecraft called Pioneers 10 and 11 and Voyagers l and 2 — which, incidentally, carry small golden greeting cards from the Earth to any space-faring interstellar civilizations which might intercept them. A society more advanced than we should be

able to ply the spaces between the stars conveniently, if not effortlessly. Over millions of years such societies should have established colonies which themselves might launch interstellar expeditions. Why are they not here? The temptation is to deduce that there are at most only a few advanced extraterrestrial civilizations — either because we are one of the first technical civilizations to have emerged, or because it is the fate of all such civilizations to destroy themselves before they are much further along.

It seems to me that such despair is quite premature. All such arguments depend on our correctly surmising the intentions of beings far more advanced than ourselves, and when examined closely I think these arguments reveal a range of interesting human conceits. For example, why do we expect that it will be easy to recognize the manifestations of very advanced civilizations? Is our situation not

closer to that of isolated societies in the Amazon basin, say, who lack the tools to detect the powerful international radio and television traffic which is all around them? Also, there is a wide range of incompletely understood phenomena in astronomy. Might the modulation of pulsars or the energy source of quasars have a technological origin? Or perhaps there is a galactic ethic of noninterference with backward or emerging civilizations.

Perhaps there is a waiting time before contact is considered appropriate, so as to give us a fair opportunity to destroy ourselves first, if we are so inclined. Perhaps all societies significantly more advanced than our own have achieved an effective personal immortality, and lose the motivation for interstellar gallivanting — which may, for all we know, be a typical urge only of adolescent civilizations. Perhaps mature civilizations do not wish to pollute the cosmos. There is a very long list of such "perhapses," few of which we are in a position to evaluate with any degree of assurance.

The question of extraterrestrial civilizations seems to me entirely open. Personally, I think it far more difficult to understand a universe in which we are the only technological civilization, or one of but a few, than to imagine a cosmos brimming over with intelligent life. Many aspects of the problem, fortunately, can be experimentally verified. We can search for planets of other stars; seek simple forms of life on such nearby worlds as Mars, Jupiter and Saturn's moon Titan; and perform more extensive laboratory studies on the chemistry of the origin of life. We can investigate more deeply the evolution of organisms and societies. The problem cries out for a long-term, open-minded and systematic search, with nature as the only arbiter of what is or is not likelv.

"It is possible that the future of human civilization depends on the receipt of interstellar messages."

If there are a millon technical civilizations in the Milky Way galaxy, the average separation between civilizations will be about 300 light-years. Since a light year is the distance which light travels in one year (a little under six trillion miles), this implies that the one-way transit time for an interstellar communication from the nearest civilization will be some 300 years. The time for a query and a response would be 600 years. This is the reason that interstellar dialogues are much less likely — particularly around the time of first contact — than interstellar monologues. It might seem remarkably selfless for a civilization to broadcast radio messages with no hope of knowing, at least in the immediate future, whether they have been received and what the response to them might be.

But human beings often perform very similar actions — as, for example, in burying time capsules to be recovered by future generations, or even in writing books, composing music and creating art intended for posterity. A civilization which had been aided by the receipt of such a message in its past might wish to similarly benefit other emerging technical societies. The amount of power that need be expended in interstellar radio communication should be a tiny fraction of what is available for a civilization only slightly more advanced than we, and such radio transmission services could be an activity either of an entire planetary government or of relatively small groups of hobbyists, amateur radio operators and the like.

Although probably no previous contact will have been achieved between transmitting and receiving civilizations, communication in the absence of prior contact is possible.

It is easy to create an interstellar radio message which can be recognized as emanating unambiguously from intelligent beings. A modulated signal ("beep," "beep-beep," . . . ) comprising the numbers 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, 17, 19, 23, 29, 31, for example, consists exclusively of the first 12 prime numbers — that is, numbers that can be divided only by 1, or by themselves. A signal of this kind, based on a simple mathematical concept, could only have a biological origin. No prior agreement between the transmitting and receiving civilizations, and no precautions against Earth chauvinism, are required to make this clear.

It is easy to create an interstellar radio message which can be recognized as emanating unambiguously from intelligent beings. A modulated signal ("beep," "beep-beep," . . . ) comprising the numbers 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, 17, 19, 23, 29, 31, for example, consists exclusively of the first 12 prime numbers — that is, numbers that can be divided only by 1, or by themselves. A signal of this kind, based on a simple mathematical concept, could only have a biological origin. No prior agreement between the transmitting and receiving civilizations, and no precautions against Earth chauvinism, are required to make this clear.

Such a message would be an announcement or beacon signal, indicating the presence of an advanced civilization but communicating very little about its nature. The beacon signal might also note a particular frequency where the main message is to be found, or might indicate that the principal message can be found at higher time resolution at the frequency of the beacon signal. The communication of

quite complex information is not very difficult, even for civilizations with extremely different biologies and social conventions. For example, arithmetical statements can be transmitted, some true and some false, and in such a way it becomes possible to transmit the ideas of true and false — concepts which might otherwise seem extremely difficult to communicate.

Such a message would be an announcement or beacon signal, indicating the presence of an advanced civilization but communicating very little about its nature. The beacon signal might also note a particular frequency where the main message is to be found, or might indicate that the principal message can be found at higher time resolution at the frequency of the beacon signal. The communication of

quite complex information is not very difficult, even for civilizations with extremely different biologies and social conventions. For example, arithmetical statements can be transmitted, some true and some false, and in such a way it becomes possible to transmit the ideas of true and false — concepts which might otherwise seem extremely difficult to communicate.

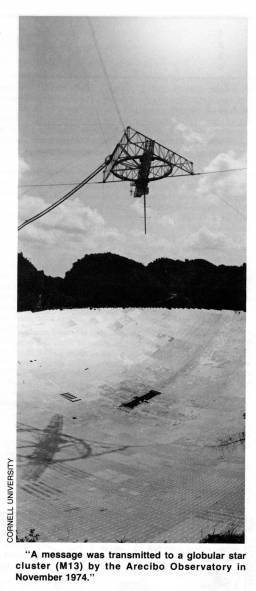

But by far the most promising method is to send pictures. The message might consist of an array of zeros and ones transmitted as long and short beeps, or tones on two adjacent frequencies, or tones at different amplitudes, or even signals with different radio polarizations. Properly arranged in rows and columns, the zeros and ones form a visual pattern — a picture similar to those an imaginative typist can create by using the letters of the alphabet as a medium. Just such a message was transmitted to space by

the Arecibo Observatory, which Cornell University runs for the National Science Foundation, in November 1974 at a ceremony marking the resurfacing of the Arecibo dish — the largest radio/radar telescope on Earth. The signal was sent to a collection of stars called M13, a globular cluster comprising about a million separate suns, because it was overhead at the time of the ceremony. Since M13 is 24,000 light years away, the message will take 24,000 years to arrive there. If anyone is listening, it will be 48,000 years

before we receive a reply. The Arecibo message was clearly not intended as a serious attempt at interstellar communication, but rather as an indication of the remarkable advances in terrestrial radio technology.

The decoded message forms a kind of pictogram that says something like this: "Here is how we count from one to ten. Here are five atoms that we think are interesting or important: hydrogen, carbon, nitrogen, oxygen and phosphorus. Here are some ways to put these atoms together that we think interesting or important — the molecules thymine, adenine, guanine and cytosine, and a chain composed of alternating sugars and phosphates. These molecular building blocks are put together to form a long molecule of DNA

comprising about four billion links in the chain. The molecule is a double helix. In some way this molecule is important for the clumsy looking creature at the center of the message. That creature is 14 radio wavelengths or 5 feet 9.5 inches tall. There are about four billion of these creatures on the third plant from our star. There are nine planets altogether, four big ones toward the outside and one little one at the extremity. This message is brought to you courtesy of a radio telescope 2,430 wavelengths or 1,004 feet in diameter. Yours truly." Especially with many similar pictorial messages, each consistent with and corroborating the others, it is very likely that almost unambiguous interstellar radio communication could be achieved even between two civilizations which have never met. Of course our immediate objective is not to send such messages, because we are very young and backward; we wish to listen.

"In the deepest sense the search for extraterrestrial intelligence is a search for ourselves."

The detection of radio signals from space would illuminate many questions which have concerned scientists and philosophers since prehistoric times. Such a signal would indicate that the origin of life is not an extraordinarily unlikely event. It would imply that given billions of years for natural selection to operate, simple forms of life generally evolve into complex and intelligent forms, as on Earth, and that such intelligent forms commonly produce an advanced technology. But it is not likely that the transmission we receive will be from a society at our own level of technological advance. A society only a little more backward than we will not have radio astronomy at all. The most likely case is that the message will be from a civilization with a far superior technology. Thus, even before we decode such a message, we will have gained an invaluable piece of knowledge: that it is possible to avoid the dangers of the period of technological adolescence we are now passing

through.

"In the last few years we have achieved an extraordinary technological capability called radio astronomy."

There are some who look on our global problems here on Earth mdash; at our vast national antagonisms, our nuclear arsenals, our growing populations, the disparity between the poor and the affluent, shortages of food and resources, and our inadvertent alterations of the natural environment of our planet mdash; and conclude that we live in a system which has suddenly become unstable, a system which is destined soon to collapse. There are others who believe that our problems are soluble, that humanity is still in its childhood, that one day soon we will grow up. The existence of a single message from space will show that it is possible to live

through technological adolescence: the civilization transmitting the message, after all, has survived. Such knowledge, it seems to me, might be worth a great price.

Another likely consequence of the receipt of an interstellar message is a strengthening of the bonds which join all human and other beings on our planet. The sure lesson of evolution is that organisms elsewhere must have had separate evolutionary pathways; that their chemistry and biology, and very likely their social organizations, will be profoundly dissimilar to anything which is familiar here on Earth. We may well be able to communicate with them because we share a common universe; because the laws of physics and chemistry and the regularities of astronomy are shared by them and by us. But they may always be, in the deepest sense, different. And when we recognize these differences, the animosities which divide the peoples of the Earth may wither. The differences among human beings of separate races and nationalities, religions and sexes are likely to be insignificant compared to the differences between all humans and all extraterrestrial intelligent beings.

If the message comes by radio, both transmitting and receiving civilizations will have in common at least the details of radiophysics. The commonality of the physical sciences is the reason that many scientists expect the messages from extraterrestrial civilizationsto be decodable. No one is wise enough to predict in detail what the consequences of such a decoding will be, because no one is wise

enough to understand beforehand what the nature of the message will be. Since the transmission is likely to be from a civilization far in advance of our own, stunning insights are possible in the physical, biological and social sciences, insights reached from the perspective of a quite different kind of intelligence.

Decoding such a message will probably be a task of years and decades, and the decoding process can be as slow and careful as we choose. Some have worried that such a message from an advanced society might make us lose faith in our own, might deprive us of the initiative to make new discoveries if it seems that there are others who have made those discoveries already, or might have other negative consequences. But I stress that we are free to ignore an interstellar message if we find it offensive. Few of us have rejected schools because teachers and textbooks exhibit learning of which we were so far ignorant. If we receive a message, we are under no obligation to reply. If we do not choose to respond, there is no way for the transmitting civilization to determine that its message was received and understood on the tiny distant planet Earth. The receipt and translation of a radio message from the depths of space seems to pose few dangers to mankind; instead, it holds the greatest promise of both practical and philosophical benefits for all of humanity.

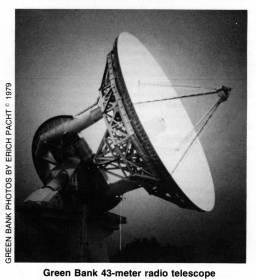

Green Bank 43-meter radio telescope

Veteran operator Ken Cottrell at the control console of the Green Bank 91-meter radio telescope

It is possible that an early message may contain detailed prescriptions for the avoidance of technological disaster, for a passage through adolescence to maturity. Perhaps the transmissions from advanced civilizations will describe which pathways of cultural evolution are likely to lead to the stability and longevity of an intelligent species, and which other paths lead to stagnation or degeneration or disaster. Perhaps there are straight-forward solutions, still undiscovered on Earth to problems of food shortages, population growth, energy supplies, dwindling resources, pollution and war. There is, of course, no guarantee that such would be the contents of an interstellar message; but it would be foolhardy to overlook the possibility.

"Humanity is still in its childhood . . . one day soon we will grow up."

There will surely be differences among civilizations which cannot be glimpsed until information is available about the evolution of many civilizations. Because of our isolation from the rest of the cosmos, we have information on the evolution of only one civilization mdash; our own. And the most important aspect of that information, the future, remains closed to us. Perhaps it is not likely, but it is certainly possible that the future of human civilization depends on the receipt and decoding of interstellar messages.

And what if we make a long-term and dedicated search for extraterrestrial intelligence and fail? Even then we surely will not have wasted our time. We will have developed an important technology, with applications to many other aspects of our own civilization. We will have greatly added to our knowledge of the physical universe. And we will have calibrated the importance and uniqueness of our

species, our civilization and other planets. For if intelligent life is rare or absent elsewhere, we will have learned something about the rarity and value of our culture and our biological patrimony, which have been painstakingly extracted over four billion years of tortuous evolutionary history.

Such a finding will stress as perhaps nothing else can our responsibilities to future generations: because the most likely explanation of negative results, after a comprehensive and resourceful search, is that societies destroy themselves before they are advanced enough to establish a high-power radio transmitting service. Thus, organization of a search for interstellar radio messages, quite apart from the outcome, is likely to have a cohesive and constructive influence on the whole of the human condition.

But we will not know the outcome of such a search, much less the contents of messages from interstellar civilizations, if we do not make a serious effort to listen for signals. It may be that civilizations are divided into two great classes, those which make such an effort, achieve contact nd become new members of a loosely tied federation of galactic communities, and those which cannot or choose not to make such an effort, or who lack the imagination to try, and who in consequence soon decay and vanish.

It is difficult to think of another enterprise within our capability and at relatively modest cost which holds as much promise for the future of humanity.

In the last few years we have achieved an extraordinary technological capability called radio astronomy.

The text of this article is reproduced by permission from SMITHSONIAN magazine May 1978. Copyright 1978 Smithsonian Institution.

Carl Sagan is the David Duncan Professor of Astronomy and Space Sciences and Director of the Laboratory for Planetary Studies at Cornell University. Before coming to Cornell in 1968, he served on the faculties of Harvard University and of the Stanford University Medical School. Born in New York City in 1934, he received his doctor's degree from the University of Chicago in 1960. His interests encompass the physics and chemistry of planetary atmospheres and surfaces, planetary exploration, origin of life on the earth, and the possibilities and means of detection of extraterrestrial life. He has been closely associated with the NASA planetary explorations involving the Mariner, Viking and Voyager missions.

Carl Sagan is the David Duncan Professor of Astronomy and Space Sciences and Director of the Laboratory for Planetary Studies at Cornell University. Before coming to Cornell in 1968, he served on the faculties of Harvard University and of the Stanford University Medical School. Born in New York City in 1934, he received his doctor's degree from the University of Chicago in 1960. His interests encompass the physics and chemistry of planetary atmospheres and surfaces, planetary exploration, origin of life on the earth, and the possibilities and means of detection of extraterrestrial life. He has been closely associated with the NASA planetary explorations involving the Mariner, Viking and Voyager missions.

Besides hundreds of scientific and popular articles, he has published a dozen books including "The Cosmic Connection: An Extraterrestrial Perspective" (Anchor Press, 1973), winner of the Campbell Award for the best science book of the year, and "The Dragons of Eden: Speculations on the Evolution of Human Intelligence" (Random House, 1977), winner of the 1978 Pulitzer Prize for non-fiction.

As one of science's most eloquent expositors, Sagan has contributed greatly to a better public appreciation of astronomy. In 1977, to improve the presentation of science on television and in motion pictures, he formed "Carl Sagan Productions: Science for the Media, Inc." An initial project is a 13-week series on astronomy.

Sagan edited the proceedings of the first international meeting on communication with extraterrestrial intelligence held in Armenia in 1971. He is also Editor-in-Chief of "ICARUS: International Journal of Solar System Studies" and a member of the Editorial Board of COSMIC SEARCH.

![[NAAPO Logo]](../../Images/NAAPOsm.jpg)

![[NAAPO Logo]](../../Images/NAAPOsm.jpg)